Archive for August 2016

No. 17 – The Strange Colour Of Your Body’s Tears (Hélène Cattet, Bruno Forzani, 2013)

Sometimes when I’m watching films for this project, I’m so inspired that I’m dying to get writing about it. And other times, I struggle to find an angle to drag out a few paragraphs (I’m looking at you, Desperately Seeking Susan). And then there’s The Strange Colour Of Your Body’s Tears, where I need to turn off all electrical equipment and sit in a darkened room for a while, because I have no clue how to write about this film. Though it does make me feel uneasy in a darkened room.

Dan returns from a business trip to find his wife Edwige missing. He asks around the building and is invited to the seventh floor where a veiled woman tells him how her husband also disappeared after being lured upstairs by strange screams and murmurs, then seemingly being murdered, which she partially witnesses by peeping through a hole he had drilled in their bedroom ceiling. Frustrated, Dan leaves and encounters a naked woman called Laura. The next day he is visited by a suspicious police inspector. This is the last point where the film seems to be interested in making any narrative sense. After that, it’s a free-for-all, with acres of possible hallucinations, hidden rooms and mysterious strangers that emerge in a visually stunning kaleidoscope of moments, few of which seem to relate to (what we thought was) the story before it became apparent that the story was not really worth thinking about. This film is to be experienced, more than understood.

The film clearly has its roots in the Giallo movement, even lifting some of its soundtrack from European horror classics. A number of brutal scenes are rendered irresistible by the astonishing production design. Knife wounds and pools of blood become erotic, their beauty almost dissolving the horror. There is a fetishistic aspect to many of the images, a nipple being teased and threatened by a knife blade, the slick leather gloves of the killer, a man’s naked torso being caressed and tortured with broken glass. Even better is the sound design, the metallic vring of knives being traced along their victim’s flesh, the deep squeak of leather, the heavy wooden roar of furniture being dragged across the floors. The woman upstairs tells her story in an eerie croak, the film suggesting she screamed herself near-mute. Dan’s door buzzer rings interminably through one sequence, to the point of audience distress, as he gets caught in a loop and seems to be spying on himself. Voyeurism recurs throughout the film, with numerous shots of eyes peering through cracks or widening in horror. The characters watch and observe each other without making any meaningful connection – Dan’s voicemails to Edwige go unheard. He follows a lead to a man who admits to travelling through the false walls in the building to live in the apartments of tenants on holiday, but will only speak to Dan through a closed door. The apartments are gloriously designed, the best and brightest of 1970s kitsch florals and dizzying geometric shapes, mustards and reds that distort and confuse the eye. We get lost within the apartment as the walls seem to curve, which is appropriate given the number of false walls and hidden rooms revealed throughout the story, and the scenes of characters hiding behind wallpaper or tearing down the walls to get at the labyrinthine space within.

There is no question that the husband and wife team of Cattet and Forzani are stylish, exhibiting impressive knowledge of cinematic history and enough of their own perspective to twist their references into something unique and memorable. But such strong imagery alone becomes somewhat tiresome when the promising narrative dissolves in favour of a succession of striking but eventually repetitive shots. Perhaps this would be less frustrating without the first twenty minutes setting up a genuinely intriguing mystery (Dan and Edwige’s apartment locked from the inside, the tenants who resist answering his questions, the inspector who suspects Dan but reveals that his own wife is missing). Leaving the plot not only unanswered but essentially ignored seems less like a bravura choice than a missed opportunity. It almost seems that the directors were too enamoured by their mise-en-scene to engage with their story, and you can only imagine how incredible the film would be if they had maintained the narrative tension alongside their aural and visual skills. It’s clear that there is a narrative thread in the film, but myself and many more qualified writers are unanimous in their inability to parse the film. The clues are there – something underlying about isolation, with characters communicating by voicemail, speaking through doors, and repeatedly seeming to have a clear connection with each other but refusing to get involved (Dan’s anger at the old woman’s story despite it seeming to provide clues about Edwige’s disappearance, the squatter knowing about the building’s hidden interiors but refusing to assist Dan). Perhaps the walls within walls represent Edwige’s hidden desires, the intrigue of doppelgangers (a threatening voicemail is revealed to be not a man but his wife, slowed down for a deeper tone, and one review counts the appearance of four different Lauras) tying in with her supposed new identity, itself echoes in the drawing of his wife being revealed as a copy of the painting in the infamous Apartment L. There’s no doubt that Cattet and Forzani have something in mind, but their film is too dense to reveal it, and the directors clearly want it that way. Maybe the greatest clue lies in the doubling of the film’s title. In the English version, it’s ambiguous as to whether it means “tears” like crying or “tears” like wounds, though the original French confirms the former. However, the film’s end reveals another new title without explanation – “L’étrange douleur des larmes de ton corps”, or “The strange pain of your body’s tears”. Not that it explains things either.

#52filmsbywomen 16 – Marjoe

Posted on: August 13, 2016

No. 16 –Marjoe (Sarah Kernochan, Howard Smith, 1972)

Marjoe is bad, not evil, and this unusually structured, Oscar-winning documentary doesn’t need too many stylish techniques to tell his strange, compelling story. Marjoe Gortner – his first name a portmanteau of “Mary” and “Joseph” – was a child prodigy in the bizarre world of Charismatic Christianity, and his parents toured him around the USA showing off The World’s Youngest Preacher to adoring crowds. However, Sarah Kenochan and Howard Smith’s documentary sees Gortner at a much different time in his life, when, tired and cynical, he decides to reveal himself, and the entire Charismatic Christianity movement, with its faith healing and speaking in tongues, as a fraud.

The film begins with Gortner narrating a general overview of his life to date and his early entry into the world of evangelism, as trained by his parents in the overenunciation and rolling Rs of the preacher lingua. He was a controversial figure, performing a marriage ceremony at 5 years old, prompting accusations that the child was a sideshow act or at worst, a grotesque corruption of what Christianity should be. His memories are intercut with footage of him surrounded by the film crew, shaking us out of our expectations of the documentary form, as we see Gortner relaxed, fooling around with the young radicals with long hair and flares, a shooting schedule hastily scrawled on a crumpled page. Gortner briefs them on how to infiltrate a tent revival without standing out too obviously, as the truth becomes clear. Gortner is ready to expose the lie he has been living. Gortner had approached Howard Smith with the idea of a behind the curtain look at evangelicalism, but Sarah Kenochan convinced Smith to attempt the film themselves rather than pass the idea to the more experienced Mayles brothers. Kenochan struggled throughout the production, despite being its driving force (Smith wasn’t a filmmaker but a journalist), as she was dismissed as Smith’s younger girlfriend. If things are bad now, imagine being 25 in 1972 and trying to control a mostly-male crew of hippies and burnouts.

The remainder of the film intercuts between Gortner’s memories, the footage of the tent revival, his conversation with the crew as he outlines the tricks of the trade, and personal footage of Gortner’s non-preaching life, where he looks and acts like any other young, famous counter-culture man in the 1970s, with a string of admirers basking in his glow. Gortner enjoys the attention, or else he is so used to being in the spotlight that his default mode is to command a room regardless of the audience. He is charming, self-aware, arrogant and at times vicious, and yet there is a wall there, even when recounting the horrors of his youth, how his mother would beat him making sure the marks wouldn’t be visible to the press or hold him under water if he made mistakes in his memorised sermons. His façade rarely breaks, and the preacher persona is second nature to him. He easily slips into the dialogue for the camera crew, mocking his own performances and predicting everyone else’s, boasting about stealing moves from Mick Jagger, and showing off for his new girlfriend as he pretends to cast out demons from their labrador. His sermons are learned, not felt – they are just a performance for him, whereas his audience is feeling it so deeply that they believe he can heal their ailments. He describes the secret codes his mother used to guide his sermons, saying “glory be to God” to signal he was running long, and choreographing his routines, opening arms each time he says Jesus, taking an emphatic step forward when he refers to the devil. Gortner seems more like a retired child star than an interlocutor of Christ.

Gortner hates the church, not the people. He relates to the congregations he visits and the joy they feel in his words. He enjoys the singing and celebration of the Pentecostal services, what he calls the “glory je to besus” angle, rather than the fire and brimstone. He says he feels guilty that every time he quits preaching, he returns for one last tour once the money runs out, and the documentary appears to be a deliberate attempt to severe his connection to the Charismatic movement altogether. He sees religion as an addiction, not just for him, returning to the guarantee of money and adulation every few years, but for the worshippers that surround him. He outlines how the church celebrates individuals who have sacrificed to donate money, giving special prayer slips to people who skipped meals so that they can give the money to Gortner or his fellow preachers. But at times his boastful nature overwhelms him, and he lapses into a dismissiveness that verges on cruelty. One scene sees him post-performance, shirtless on a bed counting the collection money, the sound of crinkling notes overwhelming the soundtrack. He laments that he doesn’t earn as much now as when he was an adorable child, and how his mother used to sew extra pockets in his suit for the admiring old ladies to fill with dollars. He mockingly performs the laying on of hands on a pretty girl, and reveals faith healing as psychosomatic, that once one or two people are convinced, other people follow.

At least Gortner is well aware of this hypocrisy. He complains how hard it is to switch between worlds, that people comment on his flamboyant clothes. We see him recline on a waterbed and laugh along to drug references. For all his guilt towards his followers, he has absolved himself of his childhood deceit, since he had no input and no choice. He criticises his father frequently, that they have no relationship, he is distant, and makes no attempt to communicate with his son. These are the only moments in the film where his façade seems to peel away. Late in the film, he attends a service where he is introduced by his father. Gortner‘s demeanour is totally different, sitting stoically as his father recounts a tale of Gortner as a boy, receiving baptism in the bath. Gortner reacts as though it is a typical, embarrassing dad story, but there is a great tension underneath. He has previously revealed to the camera that he never believed in a God. Even as a child, religion was a business.

The film won the Oscar, but it faded quickly from public memory, in case you hadn’t noticed that the Pentecostal movement’s as strong as ever. This is perhaps due to its lack of a release in the South, but definitely not helped by the fact that for a long time the film only existed as a poorly aged copy of a copy of a print. While Kernochan fought for years to be properly credited for the project, it was her temerity that ensured the film continued to exist. After buying back the rights, she was contacted by the Library of Congress who by chance had a pristine copy. Marjoe had risen again.

Throughout the film, Gortner returns to a scrapbook of newspaper clippings of his childhood infamy, maybe showing it off to the crew, maybe nostalgic himself. He explains that his parents earned millions of dollars off his performances, but he never saw any of it. But he says he has let go of bitterness towards parents and his involvement in the Charismatic movement. After all, now he believes in karma.

No. 15 – The Punk Singer (Sini Anderson, 2013)

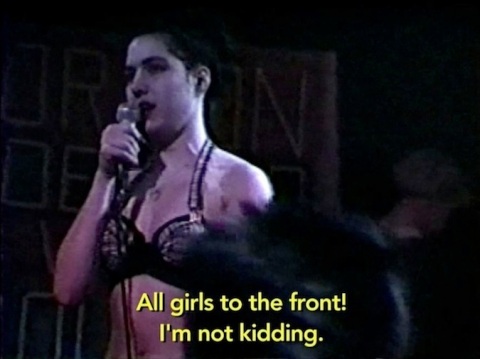

Women are rarely allowed to just be; they have to explain and justify why they are who they are, in a way that men rarely face. Amber Rose has to justify why she deserves called a whore even though she has built a career off the contours of her body. Hillary Clinton faces taunts about claiming to be a strong woman when she accepted her husband’s infidelity. Rape victims have to explain how drinking to a stupor or going home with a stranger does not permit assault. Kathleen Hanna, face of the Riot Grrrl movement, an opinionated and outspoken woman, in an era and industry who loathed those qualities from feminine lips, faced more than most. It becomes clear throughout Sini Anderson’s documentary, The Punk Singer, that she is no longer willing to play that game. Hanna is no longer interested in explaining.

Not that Hanna is hiding anything, per se. The documentary finds plenty of archival footage and willing talking heads to fill in the blanks in Hanna’s story, and Hanna herself expresses no reluctance to repeat, discuss or reveal when she feels like it. But there is a sense that for a woman of such depth and significance, the film barely scratches the surface. But perhaps after a lifetime of being cajoled by aggressive music journos to justify herself, Hanna no longer wishes to reveal any more of herself than she wants to.

Anderson makes little effort to dig into Hanna’s psyche, happy to let her subject dictate how much is discussed. Not to paint Hanna as a tyrant or Anderson as a patsy, but there is a notable difference between biographical material where the subject is a participant only, and where the subject is actively involved. This may been connected to Anderson’s efforts to complete the film, which included a Kickstarter, a benefit concert headlined by Hanna collaborator Kim Gordon, and eventually Tamra Davis, wife of Hanna’s husband’s bandmate (Beastie-in-law?), signing on as co-producer – clearly there was motivation to please Hanna’s fanbase. And while Hanna herself isn’t credited in the production, she did have unexpected input, requesting that the chosen interview subjects were largely female – which is obviously a relevant decision given Hanna’s background, but it is highly unusual for a documentary subject to dictate who is and who isn’t interviewed. There are moments where Hanna severs discussions and the film moves on, without any attempt at follow up with the other subjects to complete whatever conversation Hanna has left hanging. There is a sense that Anderson may have been overawed by her subject and the pretence at objectivity (so vital in documentary filmmaking) is lost in return for access to Hanna, which is a shame as Hanna is more than worthy of a more transparent exploration.

Of course, that criticism opens up further discussions about why we expect documentary subjects to give up their right to privacy for the pleasure of the viewer. While Hanna’s veiled references to her difficult childhood (she insists she was never raped, but refuses to discuss any further) raise and then frustrate the viewer’s curiosity, why should we be entitled to all the details? It’s Hanna’s story to tell or not tell, even if she did agree to the documentary, and it’s churlish to criticise Anderson for putting respect before traditions of the documentary form. But it is a fine line to tread between respectful film making and propaganda piece, but given Hanna’s years of dealing with the media, and their interpretations, misinterpretations and reinterpretations of her music, her politics and her words, you can’t really blame her for her decision to exert control over her image in a way the media rarely allows a woman or really any public figure to do.

And none of this is to suggest that Hanna is particularly evasive. Indeed, the film’s biggest publicity point was Hanna’s painful honesty regarding her disappearance from the music scene, as she spoke for the first time about the diagnosis of late stage Lyme disease that essentially ended Le Tigre and forced Hanna into retirement. The revelation comes late in the film, and it is shocking, not only to see footage to Hanna, up to this point so charismatic and compelling, looking so physically vulnerable during treatment, but also brought so emotionally low by not only the ordeal of her health problems, but the impact of leaving music behind and isolating herself from her bandmates to hide her illness. The film is deft in tying Hanna’s feminist beliefs to her health problems. Chronic Lyme disease is a contentious issue, with some people suggesting it is a psychosomatic illness, and Hanna likens people’s reluctance to believe her diagnosis with society’s reluctance to engage with feminist issues. As Hanna states so eloquently, “when a man tells the truth, it’s the truth. And when, as a woman, I go to tell the truth, I feel like I have to negotiate the way I’ll be perceived.”

I’m concerned that the harsh tone is disguising my own biases, which is to say I’m a big fan of Kathleen Hanna and her various music projects, and spending time in her company throughout the film is a pleasure. Over the years she has been mocked for her supposed Valley girl accent, which is endemic of the media’s reluctance to actually listen to what she has to say. Even an objective, almost critical documentary would not be able to dim the light of Hanna’s intelligence and principles, which should be inspirational to anyone who believes in gender equality, or, simply anyone moved by the power of music. Anderson’s film features admirers from all eras of contemporary feminism, from Joan Jett to Tavi Gevinson, alongside Hanna’s contemporaries and collaborator, few of whom have had such a consistently combative relationship with the media. But Hanna is an old hand at other people’s attacks, maintaining a calm but bemused tone when recounting the various scorn, assaults and death threats she and the Riot Grrrl movement have faced over the years, buoyed by the strength of her convictions. The only time she seems to waver is when recounting the time Courtney Love punched her, shaken by this unexpected woman on woman violence, perpetrated on a woman who has more for female voices in the music industry than anyone else. But then, as Hanna works on her new band, The Julie Ruin, it’ll take a lot more than the singer from Hole and a touch of Lyme disease to keep Kathleen Hanna down.